Just what's going on in my life. For more about me, visit my website www.AnuragJain.com

Contact me

(Calls/SMS' welcome, but I won't reply to SMS')

# Yahoo Messenger

#

ajain@iimb.ernet.in

# anuragkjain

@yahoo.com

# +91-9886178995

(Online

24 hrs but may not be on machine all the time. You can be assured of a

response, though!)

Aviation Blogs

- Aviation India

- Devesh Agarwal

- Kapil Bhargava

Blogs I know

- AlbumOfTheMoment

- Alternative

Perspective

- Anand Sridharan

- Anuradha Goyal

- Anurag Gupta

- Aqua

- Desi Bridget Jones

- Dream Reem

- Emergic

- Gary

- Google Blog

- IS Research

- Oneirodynic

- Life in a HOV Lane

- Nirantar

- Pankaj Bagri

- PhDweblogs

- Prof Sadagopan

- Rajeev Sharma

- Radio Monitors

India

- RecordBrother

- Requiem for a

Dream

- Retail India

Business News

- Research Blogs

- Rojnamcha

- Scopitones

- Sling Inc.

- Slowread

- TheBuckStopsHere

- The Startup Journey

- VC Circle

- Venture Intelligence

IIMB Blogs

- Aadisht Khanna

- Amit Gandhi

- Aragorn (Nikhil

Gurjar)

- Deepak Devarajan

- Elysia

- IIM-B Thinks...

- Illusionaire (Kima)

- Gautam Srivastava

- Guhan

-

Manu Bharadwaj

- Meenakshi Shankar

- Nikhil Ramesh

- PGSM Blog

- Pradeep Shastry

- Sridhar Raman

- Sudheer Narayan

- Sumit Mittal

- Twisted Shout

(IIMB's Blog)

- Varathkanth

- Vinod ChikkaReddy

- Viswanathan RJ

RSS Feed:

1) Official Atom XML Feed

2)

Powered by

RSSify at WCC

Archives

*October 2002

*November 2002

*December 2002

*January 2003

*February 2003

*April 2003

*May 2003

*June 2003

*July 2003

*August 2003

*September 2003

*October 2003

*November 2003

*December 2003

*March 2004

*April 2004

*May 2004

*June 2004

*July 2004

*August 2004

*September 2004

*October 2004

*November 2004

*December 2004

*January 2005

*February 2005

*March 2005

*April 2005

*May 2005

*June 2005

*July 2005

*August 2005

*September 2005

*October 2005

*November 2005

*December 2005

*January 2006

*February 2006

*May 2006

*June 2006

*July 2006

*August 2006

*September 2006

*October 2006

*November 2006

*December 2006

*January 2007

*February 2007

*March 2007

*April 2007

*May 2007

*June 2007

*July 2007

*August 2007

*September 2007

*October 2007

*April 2008

*May 2008

*June 2008

*July 2008

*August 2008

*September 2008

*October 2008

*November 2008

*December 2008

*January 2009

*February 2009

*August 2022

![]()

Blog Keywords:

Bangalore

IIM Bangalore

IIMB

Cultural Events

Management Education

Entrepreneurship

B-Schools

India

Friday, February 18, 2005

Comments: Post a Comment

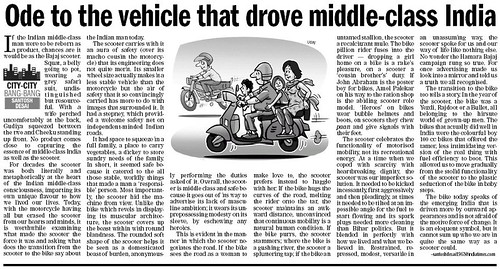

Ode to Scooter. (Aka Scooter Vs Babes & Bikes).

Recently, in the Times of India there was this real neat article on the way Scooter has been a part of middle-class Indians' lives. I found it particularly interesting because I myself drive a scooter. An antique one at that: LML Vespa 1990 model! Registration # UP-11 5018. I love my scooter, I do. However, in tune with the spirit of the article, my scooter is becoming a bit of a bottleneck when it comes to attracting 'chickas'. Babes would rather walk with me or offer me a ride in their car (Role-reversal version of Aaja meri gaadi mein baith jaa) to the planned destination. But they wouldn't get on my scooter, for the fear lest somebody should see them on a lowly-scooter and their social standing ruined! Its actually baffling because when you think of it deeply, (most of the) girls are supposed to be this 'family types' (at least in the long run) [okay, enough of stereotyping]. And, scooter carries a lovey-dovey family sorta image. Then logically, it should be a 'chick-magnet' (a friend of mine once used this term for laptop!). Only, it ain't! There you have it. Logic humbled at the altar of consumerism! Damn the booming economy!!

And what the heck does the article mean by: If the bike sees the road as a woman to make love to, the scooter prefers instead to haggle with her. Baloney. Bollocks. Billions of Blistering Barnacles. Ten Thousand Thundering Typhoons. Scooter can make love to the road as well as bike can, and better! I rest my case.

Here's a pic of me and my Vespa. And, tons of guys. (By now, you know why I am with guys and not babes) Hey, wait a minute. I just realized that those tons of guys are totally hiding my Vespa. Are they ashamed too? Maaaan!

Recently, in the Times of India there was this real neat article on the way Scooter has been a part of middle-class Indians' lives. I found it particularly interesting because I myself drive a scooter. An antique one at that: LML Vespa 1990 model! Registration # UP-11 5018. I love my scooter, I do. However, in tune with the spirit of the article, my scooter is becoming a bit of a bottleneck when it comes to attracting 'chickas'. Babes would rather walk with me or offer me a ride in their car (Role-reversal version of Aaja meri gaadi mein baith jaa) to the planned destination. But they wouldn't get on my scooter, for the fear lest somebody should see them on a lowly-scooter and their social standing ruined! Its actually baffling because when you think of it deeply, (most of the) girls are supposed to be this 'family types' (at least in the long run) [okay, enough of stereotyping]. And, scooter carries a lovey-dovey family sorta image. Then logically, it should be a 'chick-magnet' (a friend of mine once used this term for laptop!). Only, it ain't! There you have it. Logic humbled at the altar of consumerism! Damn the booming economy!!

And what the heck does the article mean by: If the bike sees the road as a woman to make love to, the scooter prefers instead to haggle with her. Baloney. Bollocks. Billions of Blistering Barnacles. Ten Thousand Thundering Typhoons. Scooter can make love to the road as well as bike can, and better! I rest my case.

Here's a pic of me and my Vespa. And, tons of guys. (By now, you know why I am with guys and not babes) Hey, wait a minute. I just realized that those tons of guys are totally hiding my Vespa. Are they ashamed too? Maaaan!

[Tons of guys. From back to front: Sapan (ChE, MS, BP Maryland), Yash (Electronics, IITK, IES, IIMC, Evalueserve), Me (the dork), Vishad (Electronics, IITK, Business, Noida)]

Now, admittedly, there have been mishaps when it comes to girls and my scooter: A flat at 0100 hrs in the middle of nowhere; A broken clutch-wire at 0030 hours - as a result of which my Vespa is prancing around like a wild, out-of-control, waiting-to-be-tamed horse. Mind you, all this while with a pillion! (Actually in this particular case, for all my scooter-jingoism, I dont really blame her for saying no to my scooter for ever and till the end of the time). But hey, comeone after all its a machine. A lovely one at that! During my Kanpur visit, when I met Mr Lohia, owner of LML group that makes LML Vespa, rather than wasting time talking business, I should have given all this useful feedback: How to make scooter attractive to babes. That one-point strategy could be the revival of scooter business. McKinseys and BCGs of the world can not give you that strategic insight!

Anyways, what the heck, I choose my scooter over girls (I can see that day ain't far when: Main aur mera Vespa, aksar yeh baatein karte hain..)

Enough ranting. Point made. Nobody hurt. Over to the article (Thanks Santosh for such a fantastic piece).

Ode to the vehicle that drove middle-class India0 comments

14 Feb 2005, Times of India.

If the Indian middle-class man were to be reborn as a product, chances are it would be as the Bajaj scooter. Squat, a belly going to pot, wearing a grey safari suit, undist i n g u i s h e d but resourceful. With a wife perched uncomfortably at the back, Gudiya squeezed between the two and Cheeku standing up front. No product comes close to capturing the essence of middle-class India as well as the scooter.

For decades the scooter was both literally and metaphorically at the heart of the Indian middle-class consciousness, imparting its own unique flavour to how we lived our lives. Today, with the motorcycle having all but erased the scooter from our hearts and minds, it is worthwhile examining what made the scooter the force it was and asking what does the transition from the scooter to the bike say about the Indian man today.

The scooter carries with it an aura of safety (over its macho cousin the motorcycle) that its engineering does not quite merit. Its smaller wheel size actually makes it a less stable vehicle than the motorcycle but the air of safety that it so convincingly carried has more to do with images that surrounded it. It had a stepney, which provided a welcome safety net on independent-minded Indian roads.

It had space to squeeze in a full family, a place to carry vegetables, a dickey to store sundry needs of the family. In short, it seemed safe because it catered to the all those stable, worldly things that made a man a 'responsible' person. Most importantly, the scooter hid the machine from view. Unlike the bike which revels in displaying its muscular architecture, the scooter covers up the beast within with rotund blandness. The rounded soft shape of the scooter helps it be seen as a domesticated beast of burden, anonymously performing the duties asked of it. Overall, the scooter is middle class and safe because it goes out of its way to advertise its lack of masculine ambition; it wears its unprepossessing modesty on its sleeve, by eschewing any heroics.

This is evident in the manner in which the scooter negotiates the road. If the bike sees the road as a woman to make love to, the scooter prefers instead to haggle with her. If the bike hugs the curves of the road, melting the rider onto the tar, the scooter maintains an awkward distance, unconvinced that continuous mobility is a natural human condition. If the bike purrs, the scooter stammers; where the bike is a gushing river, the scooter a spluttering tap; if the bike an untamed stallion, the scooter a recalcitrant mule. The bike pillion rider fuses into the driver - dropping a girl home on a bike is a rake's pleasure, on a scooter a 'cousin brother's' duty. If John Abraham is the poster boy for bikes, Amol Palekar on his way to the ration shop is the abiding scooter role model. 'Heroes' on bikes wear bubble helmets and boots, on scooters they chew paan and give signals with their feet.

The scooter celebrates the functionality of motorised mobility, not its recreational energy. At a time when we coped with scarcity with heartbreaking dignity, the scooter was our imperfect solution. It needed to be kicked incessantly, first aggressively and then pleadingly, at times it needed to be tilted at an impossible angle for the fuel to start flowing and its spark plugs needed more cleaning than Bihar politics. But it blended in perfectly with how we lived and what we believed in. Restrained, repressed, modest, versatile in an unassuming way, the scooter spoke for us and our way of life like nothing else. No wonder the Hamara Bajaj campaign rung so true. For once advertising made us look into a mirror and told us a truth we all recognised.

The transition to the bike too tells a story. In the year of the scooter, the bike was a Yezdi, Rajdoot or a Bullet, all belonging to the hirsute world of grown-up men. The bikes that actually did well in India were the colourful boy 100 cc bikes that offered the tamer, less intimidating version of the real thing with fuel efficiency to boot. This allowed us to move gradually from the stolid functionality of the scooter to the plastic seduction of the bike in baby steps.

The bike today speaks of the emerging India that is driven more by outward appearances and is not afraid of the motive force of change. It is an eloquent symbol, but it cannot sum up who we are in quite the same way as a scooter could.

- santoshdesai1963 AT indiatimes.com

Comments: Post a Comment